Established in 1905, Rolex is world-famous for tough, reliable watches. This reputation largely comes from the Oyster case, Rolex’s patented waterproof design. Introduced in 1926, the Oyster was a radical step in watchmaking. Rolex had found a way to seal a wristwatch so water and dust could not enter. The brand’s own account calls it a “revolutionary new case design” that kept the watch movement inside an airtight chamber. This hermetic seal allowed the watch to withstand splashes, rain, and even prolonged immersion, which older designs could not handle.

I am a fan of Rolex, not so much as a hopeful “future owner” (I do want a no-date Submariner, but the other models don’t really appeal), but as an admirer of the business model that Hans Wilsdorf built. He was a marketing genius. At a time when no one was putting the manufacturer’s name on the dial, he did. In addition, he used the media effectively and was sometimes “flexible” with his claims. To quote Mark Twain, Wilsdorf never let the truth get in the way of a good story. This is particularly the case with the Oyster design. It wasn’t, as Wilsdorf claimed, the first waterproof watch, but it was and still is the most famous.

Early challenges in waterproof designs

The early 20th century saw a seismic shift in personal timekeeping. Wristwatches were becoming increasingly more popular. However, these delicate mechanisms faced significant challenges from the elements. Water and dust could easily infiltrate the cases, causing damage and affecting timekeeping. Watchmakers of the time struggled to create timepieces that could withstand these elements. Initial attempts to create “waterproof” watches often fell short of providing true protection in aquatic conditions (The History of Waterproof Watches at Oracle Time).

The origins of the Oyster design

Hans Wilsdorf believed a truly waterproof watch would sell well. In 1926, he asked case-maker C.R. Spillmann & Co to create one. The result was a three-part case. A threaded bezel with a crystal, a middle case holding the movement, and a screw-down caseback formed a sealed box. Rolex secured a patent on this design in 1926 (CH120851), covering the screw-down bezel and back. The company also patented an improved screw-down winding crown (CH120848) with an internal clutch. This clever clutch meant the crown could always be tightened even when the mainspring was fully wound. In short, Rolex developed a watch case that could be closed up tightly like an oyster shell (Rolex Oyster at Vintage Watchstraps).

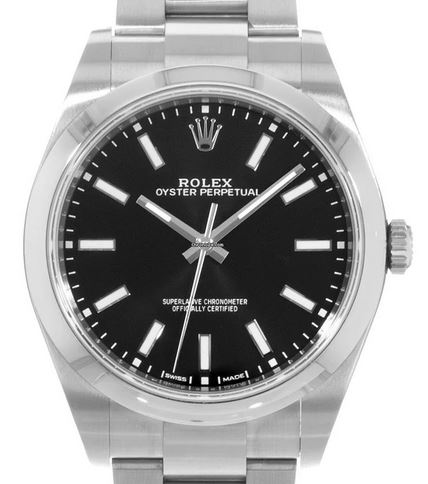

The very first Oyster cases were octagonal in shape and made of 9-carat gold. This 1926 model was only 33 mm wide, which is small by today’s standards. But it packed all the key features: a screw-down bezel, a screw-down back, and that new screw-down crown. When all these parts were screwed together, the design created a sealed vacuum inside the case. Dust and moisture simply could not get in. Rolex even noted that the case would compress “tightly together like an oyster shell,” hence the name Oyster.

Rolex promoted the Oyster’s origins actively. According to Mikrolisk, the trademark “Oyster” was registered on 29 July 1926, just days after the patent was filed. This showed how fast Wilsdorf moved once the design was ready. He clearly realised the market potential. By late 1926, the first Oysters were ready to wear. The early ads showed the fluted bezel and winding crown that would become Rolex’s signature look.

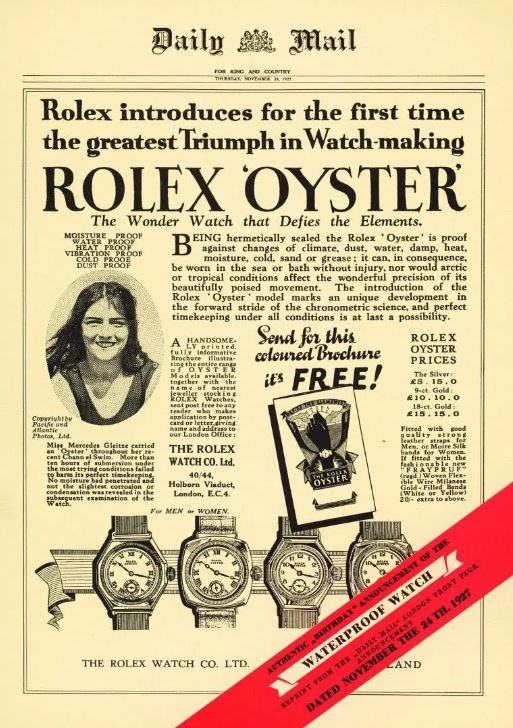

The English Channel, a marketing masterpiece

To prove his new case really worked, Wilsdorf staged a high-profile test. In 1927, Rolex sponsored British swimmer Mercedes Gleitze. She attempted to swim the English Channel wearing a Rolex Oyster around her neck. It was a dramatic 21-mile swim in frigid water. After more than ten hours battling waves, she had to stop just shy of the French coast. However, the Rolex survived the ordeal intact. When independent witnesses opened the watch afterwards, they found no water inside. The movement still ran perfectly. This real-world test made headlines. It showed that the Oyster case could handle real pressure, not just lab tests.

Gleitze tried again a few days later. This time, she succeeded and became the first British woman to cross the Channel. By then, Rolex had already built a legend for the Oyster. They dubbed her watch the “Companion Oyster” of the “Vindication Swim” and used the feat to promote the brand. The publicity worked. Newspapers and magazines wrote about a watch that still ran smoothly after a marathon swim. Rolex famously boasted that the Oyster could keep a dive watch’s movement “in flawless working order” even after full submersion. These daring marketing stunts helped establish Rolex’s reputation. As one historian notes, the Gleitze Oyster essentially “propelled Rolex into the public eye,” setting the stage for the company’s future success (Mercedes Gleitze at the BBC).

Innovations and patents

Behind the famous swim, the Oyster case involved significant technical work. Rolex didn’t simply adapt an existing idea; they patented new features. In addition to the screw-down case, they took a novel step with the crown. Earlier designs (like a 1925 patent by Perret and Perregaux) had a reverse-threaded crown but no clutch. That had proven impractical because a fully wound watch could not be sealed again. Rolex’s solution was the internal clutch that always let the crown be screwed down. This was probably the most significant breakthrough in the history of waterproof watches.

Rolex also made sure that anyone working on watches could tighten the case securely. In 1929, Wilsdorf filed a patent (GB353722A) for a special tool to tighten case backs and bezels (How Rolex Became Rolex at Wind Vintage). This meant watchmakers could seal each Oyster case exactly as intended, improving its water resistance. Rolex considered these refinements crucial. They even shared some tools with customers who did their own maintenance, reflecting Wilsdorf’s belief in fine detail and user confidence.

Early Rolex cases were made from precious soft metals like gold and silver. This led to a small problem. Daily winding meant unscrewing the crown many times. Since the crown tube was also metal, it could wear down. The fix was to use a hard steel crown tube in later watches. This change kept the crowns tight for longer without leakages.

Another innovation came in the years after the first models. Rolex added a dust-proof cover over the winding crown on some watches. These little caps unscrewed when winding and resealed afterwards. This way, even if someone forgot to screw the crown down fully, the dust cap kept grit and water out. By 1931, Rolex had combined its new automatic winding system with the Oyster case. The result was the first truly self-winding waterproof wristwatch, called the Oyster Perpetual (I think that deserves a separate post). Rolex claimed it could be wound indefinitely by the wearer’s wrist while remaining sealed against the elements.

The Oyster case in the 1930s and beyond

The Oyster case quickly became a core part of Rolex’s identity. Over the 1930s and beyond, Rolex applied it to many models. It proved its worth not just in swimming pools but in extreme environments. The company partnered with explorers and navies to push the design further. Submarine crews and early scuba divers provided feedback: they needed even tougher cases for deeper water. Rolex responded by reinforcing the case. They used extra-thick casebacks and even patented expanding ribs to let the back flex under high pressure without breaking. By 1930, Rolex was producing special “Deep Sea” Oysters. One model carried a Club Zulu logo and was tested in the cold North Sea (Rolex Oyster case at Bob’s Watches).

During World War II, British Royal Navy divers trusted Rolex Oysters in combat. These watches became part of the standard kit for frogmen and commandos. In 1953, Rolex introduced the Submariner. It had an oversized crown and a classic round Oyster case. This watch was rated waterproof to 100 metres (330 feet). Rolex advertised it as suitable for deep-sea exploration. A few years later, in 1967, the Sea-Dweller took things further: its Oyster case with a special helium escape valve was rated to 610 metres (2000 feet) (Sea-Dweller at Wikipedia). These developments all built on the same Oyster core, a screw-down crown and a screw-caseback case.

The Oyster case today

After nearly a century, the Oyster case remains an icon of watch design. Modern Rolex models may have new materials (ceramic bezels, advanced gaskets, etc.), but they all trace their roots to that 1926 invention. After the Rolex marketing machine showed that a watch could truly resist water, other brands had to follow or fall behind. Waterproof watches became standard for any serious tool watch, from divers to pilots.

Related content

Case materials at Rolex.

Leave a Reply