I must admit, I have never seen an Omega Marine watch in person. They are not on my immediate list for collection, because I am not a massive fan of dive watches, although the Rolex no-date Submariner is an exception. However, I am a big fan of Omega in general, particularly the Seamaster and Speedmaster ranges. I have been writing extensively about Omega recently, and thought the Omega Marine was worth introducing. Here is what I have uncovered in recent weeks. I apologise in advance for the sprawling nature of this post. Any questions? Please let me know in the comments below.

Challenges in early 20th-century watchmaking

The early 20th century saw a seismic shift in personal timekeeping. Wristwatches were becoming increasingly more popular. However, these delicate mechanisms faced significant challenges from the elements. Water and dust could easily infiltrate the cases, causing damage and affecting timekeeping. Watchmakers of the time struggled to create timepieces that could withstand these elements. Initial attempts to create “waterproof” watches often fell short of providing true protection in aquatic conditions. In 1932, a groundbreaking timepiece emerged that would redefine the standards of water resistance. The Omega Marine arrived, marking a pivotal moment in watchmaking history. It gained recognition as the world’s first true dive watch, a distinction earned through its innovative design and rigorous testing. The Omega Marine moved beyond basic water resistance to genuine underwater capability (Wet and dry precision at Omega Chronicle).

Water resistant watches

The journey towards truly waterproof watches began with a focus on protecting pocket watches. An early example of this effort was in 1851. Pettit & Co. showcased a watch suspended in a globe filled with water. This demonstration aimed to prove the watch’s resistance to seawater and other liquids. Later, in 1891, François Borgel patented a water-resistant case designed specifically for wristwatches. This design featured threaded parts to improve sealing. In 1915, Tavannes introduced the “Submarine” watch. Advertisements at the time claimed it was both dustproof and waterproof. In 1921, Jean Finger submitted a patent (brevet) CH 89276 introducing a novel “protective box” or double-case design for wristwatches. Although without gaskets it wasn’t truly waterproof, and it was inconvenient to wind the watch as the bezel and crystal needed to be removed to access the crown (The History of Waterproof Watches at Oracle Time).

These initial attempts often involved bulky external cases and rudimentary sealing methods that provided limited protection against water ingress. The evolution of waterproof watches was a gradual process. Early solutions, while innovative for their time, often lacked the robustness needed for true underwater use.

The Rolex Oyster case

A significant moment in the development of waterproof wristwatches came in 1926. Rolex patented its famous Oyster case. The Oyster case featured a hermetically sealed design. It also incorporated a screw-down crown, enhancing its water resistance. To promote the Oyster’s capabilities, Rolex famously equipped Mercedes Gleitze with one during her English Channel swim in 1927. After her successful swim, Rolex heavily advertised the Oyster as the first truly waterproof wristwatch. The Rolex Oyster was a major advancement in creating a reliable waterproof wristwatch for everyday wear. Its marketing success and patented design established a benchmark. Other manufacturers, including Omega, had to consider and innovate around this standard. As effective and popular as the Rolex Oyster was, it wasn’t a true dive watch (The world’s first dive watch at The Naked Watchmaker).

In response to the growing demand for water-resistant timepieces and the benchmark set by Rolex, Omega introduced the Marine in 1932. The development of this innovative watch was based on a Swiss patent (CH 146310) granted to Louis Alix of Geneva. Omega assigned the watch the reference number CK 679. The company aimed to create a timepiece specifically tested for underwater use. This was a key differentiator from earlier “waterproof” watches. Omega was determined to develop a watch that did not infringe on Rolex’s already established patent for the Oyster case. This strategic decision led to the development of a unique waterproofing system.

The Omega Marine case design

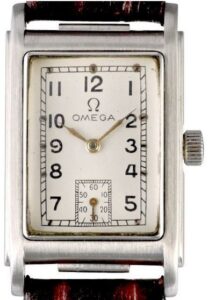

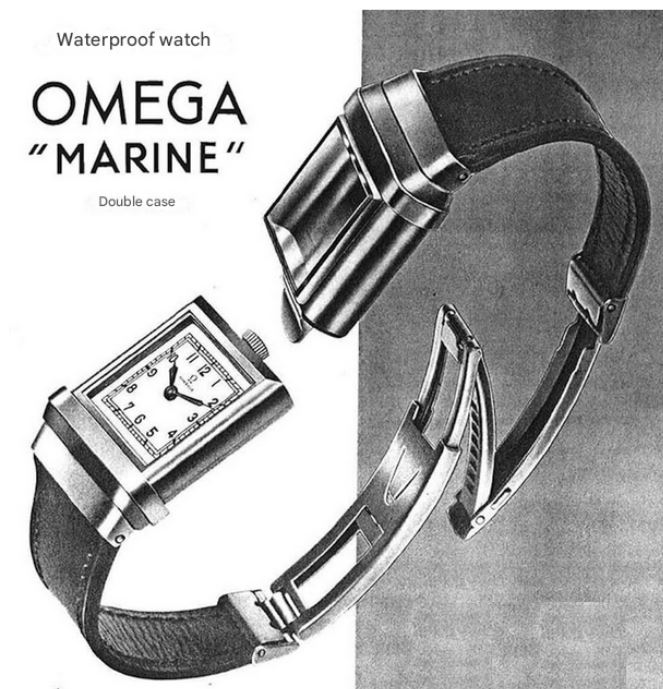

The Omega Marine distinguished itself with its unique two-part stainless steel case design. This double-casing system was central to its water-resistant capabilities. The watch mechanism, including the dial and hands, was housed within an interior case. This inner case was then designed to slide snugly into a second, outer case. To ensure a watertight seal, a gasket was placed in a groove on the interior case. When the inner case slid into the outer case, this gasket would come into contact with the end of the outer case, effectively preventing water from entering. The two parts of the case were held together by a spring clip located on the back of the outer case. This clip provided the initial pressure needed to create the seal between the inner case, the gasket, and the outer case (1930s Omega Marine at Hodinkee).

An ingenious aspect of this design was how water pressure at greater depths enhanced the waterproofness. As the watch descended underwater, the increasing external water pressure would press the two parts of the case together even more firmly. This increased pressure on the gasket strengthened the seal, making it even more watertight. Early versions of the Omega Marine used a cork seal to achieve this. Later models incorporated rubber gaskets, which likely offered improved durability. Another distinctive feature was the placement of the crown. Unlike many contemporary wristwatches, the Omega Marine had its crown located on the top section of the inner timepiece, similar to a pocket watch. This crown was then protected by the outer casing. The double-casing system was a clever solution. It allowed Omega to create a water-resistant watch without directly copying Rolex’s patented screw-down crown.

Period advertising reported the following features

Double case: Interior case houses the movement and slides into an exterior case.

Sealing mechanism: Gasket (leather initially, later rubber) on the interior case creates a watertight seal with the exterior case.

Securing mechanism: Spring clip on the back of the exterior case holds the two parts together.

Pressure enhancement: Water pressure increases the tightness of the seal at greater depths.

The Crown position is located at the top of the inner case, similar to a pocket watch.

The outer case is fitted with a sapphire crystal (ten times as strong as ordinary glass).

While I have no doubt that these features made the Omega Marine suitable for diving, it still had the inconvenience of needing to remove the outer case to wind the watch. This was the flaw that prevented the Jean Finger solution from being widely accepted. Who wants that level of inconvenience on a daily basis?

Scientific testing

To prove its capabilities, the Omega Marine underwent extensive testing. In 1936, an Omega Marine was submerged in Lake Geneva to a depth of 73 metres for a duration of 30 minutes. This test aimed to verify its water resistance in a real-world scenario. The following year, in 1937, the Swiss Laboratory for Horology conducted further tests. These laboratory tests confirmed that the Omega Marine was completely waterproof to an impressive depth of 135 metres. These tests were significant as they were the first verified demonstrations of a wristwatch’s ability to withstand the pressures encountered during diving. This testing and certification process was crucial in establishing the Omega Marine’s reputation as a genuine dive watch. It provided concrete evidence of its underwater capabilities, setting it apart from earlier watches with less stringent testing (First dive watch at Vintage Watchstraps).

I think it is important to note that these were “laboratory” tests. Although I have no doubt that the Omega Marine was significantly more water-resistant than any other watch of the period, it probably wouldn’t stand up to the definition of a dive watch today. It is worth keeping in mind that scuba wasn’t widely available until the 1940s, so diving as we know it, just simply wasn’t an option in the 1930s.

Notable figures

The Omega Marine gained further credibility through its association with pioneers of underwater exploration. Commander Yves Le Prieur, a French Naval Officer and the inventor of the aqualung (SCUBA), was known to wear the Omega Marine while diving. William Beebe, an American naturalist and explorer who began underwater exploration in the late 1920s, also wore and publicly endorsed the watch. In 1936, Beebe made a dive in the Pacific Ocean while wearing an Omega Marine, reaching a depth of 14 metres. He reported that the watch successfully withstood the pressure at that depth. Beebe praised its tightness against water and dust, as well as its resistance to corrosion, considering it a significant advancement for watchmaking science. The endorsements from these prominent figures in early underwater exploration provided significant validation for the Omega Marine’s capabilities.

Société Suisse pour l’Industrie Horloger (SSIH)

Omega and Tissot merged in 1930 as a result of the global financial difficulties of the period. They maintained separate factories and made similar but slightly different movements. Tissot focused on the affordable end of the market. There was some crossover between the two, and movements were often shared, albeit with minor differences. For example, an Omega calibre may have a Breguet overcoil balance spring, while the Tissot version used a flat balance spring (SSIH at The Swatch Group). There were also instances where the watch was printed with both names, “Omega Watch Co. Tissot”. There have been noted examples, although rare, with the Marine displaying both names of the movement and case.

Marine calibres 19.4 T1 and 19.4 T2

The Omega Marine was powered by manually wound movements. Initially, it featured the calibre 19.4 T1, which was created in 1930. Later, Omega upgraded the watch to the improved calibre 19.4 T2, introduced in 1935. These movements were round in shape, despite the rectangular case, and had a diameter of 19.4 millimetres. They were available with either 15 or 17 jewels and operated at a frequency of 18,000 vibrations per hour (19.4 T1 and T2 at Vintage Watchstraps). Notably, the Omega Marine never incorporated an automatic winding mechanism. Omega did not introduce its first automatic movements until 1943. The absence of an automatic movement, despite its potential advantages for a dive watch, reflected the prevailing technology of the era. Neither of these movements included shock protection. Although the first commercially viable shock protection systems for watches arrived during the mid-1930s, it wasn’t until the 1950s that anti-shock systems became widespread.

The innovative double-case design of the Omega Marine was based on a Swiss patent granted to Louis Alix from Geneva. It is believed that Omega engaged a French designer, likely Louis Alix himself, to develop a solution that would not infringe upon Rolex’s existing patents. The cases for the Omega Marine were manufactured by the company of Frédéric Baumgartner, also based in Geneva. While Baumgartner’s name did not appear on the cases, his company’s hallmark can be found on gold versions (reference OJ 679) of the Omega Marine. Omega, as the established watch manufacturer, took on the responsibility for the overall design, production, testing, and marketing of the Omega Marine.

The Omega Marine vs the Rolex Oyster

The Omega Marine and the Rolex Oyster represented distinct approaches to achieving water resistance in a wristwatch. The Rolex Oyster employed a screw-down crown and a hermetically sealed case to keep water out. In contrast, the Omega Marine utilised a unique double-casing system. This system relied on a cork (later rubber) seal and the innovative feature of pressure enhancement at greater depths. A key difference between the two was the extent of testing for underwater use. The Omega Marine underwent specific and rigorous testing, earning certification for diving to a significant depth of 135 metres. The early Rolex Oyster, while waterproof for swimming and everyday exposure, was not initially tested to the same depths.

Historically, Rolex’s marketing often asserted the Oyster as the first truly waterproof wristwatch. However, the documented existence and depth testing of the Omega Marine challenge this claim. While the Rolex Oyster achieved widespread commercial success as a waterproof watch for general use, the Omega Marine’s focus on depth testing and its proven capabilities arguably positions it as the first true dive watch (Rolex Submariner Vs Omega Seamaster at Watchfinder).

Production of the Omega Marine

The original Omega Marine was introduced to the public in 1932. In 1939, Omega also released the Omega Marine Standard, reference CK 3635. This Marine Standard had a simpler design than the original 1932 Omega Marine, without the outer case. It also had the crown on the outside of the case, so it was more convenient to wind the watch and set the time. The Omega Marine Standard used the T17, a manual wind calibre with 15 jewels (17-jewel versions exist) beating at 18,000 vph. It also boasted an impressive 60 hours of power reserve (T17 movement at Fratello).

The original Omega Marine was in production from 1932 to 1939. The Omega Standard, introduced in 1939, had a much shorter production run, only lasting a few years. They were phased out because of improving technology and the awkward design. The original Marine’s inner-outer case system was costly and required frequent servicing to maintain its water resistance. By the late 1940s, Omega had adopted O-ring seals and simplified cases, offering equal or better water resistance more economically. In 1948, Omega launched the Seamaster, using technology adopted from the Dirty Dozen watches of WW2. In 1957, they introduced the Omega Seamaster 300, a professional dive watch, rated to 200 m (Omega Seamaster at Chronopedia).

Summary

The Omega Marine represents a significant milestone in the history of watchmaking. It was a pioneering endeavour in the creation of a wristwatch specifically designed for diving. Its association with early luminaries of underwater exploration, such as Commander Yves Le Prieur and William Beebe, further solidified its historical importance. The innovative double-case design of the Omega Marine laid the groundwork for future advancements in the development of dive watches. In recognition of its historical significance, Omega released a reproduction of the watch, the Marine 1932, as part of its Museum Collection in 2007. Despite some practical considerations related to winding and maintenance, the Omega Marine remains a highly sought-after and historically important timepiece for collectors.

Although I titled this article “The Omega Marine: the first true dive watch”, after all of this research, I’m not actually convinced that it was. I think from Omega’s perspective, the Seamaster 300 was probably the first true “professional dive watch”. Possibly, I may be a bit biased, as a die-hard Seamaster fan, but I just think the awkward design of the Omega Marine truly held it back. I welcome comments to the contrary below.

Related content

Omega Chronicle, the history of Omega.

Leave a Reply