Longines relaunched the Ultra-Chron in 2022. It is a near-perfect revival of the high-frequency range that first appeared in the 1960s. We saw a vintage Ultra-Chron on one of our recent expeditions to an Antiques and Collectors Fair. There wasn’t a known service history for this particular example, so it wasn’t purchased. However, it did inspire us to do some research behind the Ultra-Chron range. Below is what we uncovered about the history behind high-frequency watches and the significance of the Longines Ultra-Chron.

What is frequency?

A mechanical watch movement includes a power source (the mainspring), a transmission system (the gear train), and a regulator (the escapement, balance wheel, and hairspring). The power flows from the mainspring, via the gear train, to the escape wheel. The resulting oscillations of the balance wheel is where the power is ultimately released and the time is manifested. Each time the balance wheel swings in a given direction, its roller jewel knocks the lever, unlocking the escape wheel. The escape wheel delivers an impulse to the balance via the lever, powering a new vibration, before locking once more. This process takes place several times per second in a mechanical wristwatch and is typically known as the frequency. This is measured in Hertz (Hz) or vibrations (or beats) per hour.

18,000 vibrations per hour (vph) / 2.5 Hz was the most typical frequency for early wristwatches and pocket watches. 19,800 vph (≈2.75 Hz) was adopted in mid-20th-century watches as an incremental step toward better precision. By the late 1950s and 1960s, higher frequencies such as 21,600 vph (3 Hz) became increasingly common, offering a balance between accuracy and durability.

A “high-frequency” mechanical watch is generally considered any movement running at 36,000 vibrations per hour (vph), or 5 Hz.

The pros and cons of High-Frequency movements

High-frequency movements offer clear benefits. Their oscillators divide time into smaller spans. This provides a higher resolution for timekeeping. A 5 Hz movement can measure time to a tenth of a second. A slower 4Hz movement can only manage an eighth of a second. The increased frequency results in greater precision. High-frequency watches recover faster from impact, so it takes less time to return to its normal frequency. This makes the movement less susceptible to shocks.

There are also distinct drawbacks to high-frequency movements. The high speed causes increased wear on components. The greater friction leads to faster lubricant breakdown, and the movements consume more energy. This results in a shorter power reserve.

The purpose of high-frequency evolved over time. In the 1960s, it was a practical pursuit of supreme accuracy, which gave a competitive advantage in sports timing. Today, as no mechanical watch can match a modern quartz watch’s accuracy, high-frequency watches are a showcase of technical skill. The appeal is about the pinnacle of mechanical achievement. Collectors accept the cons, such as a shorter power reserve, and view them as part of the watch’s high-performance nature.

The pursuit of precision

The pursuit of accuracy in watchmaking has always been closely tied to the regulation of frequency within a watch movement. Since the 17th century, when Christiaan Huygens introduced the balance spring, watchmakers have sought to refine oscillation systems to achieve greater precision. They realised that a higher frequency in the balance wheel generally results in improved timekeeping. Robert Hooke, a contemporary of Huygens, also experimented with balance springs and escapements, contributing to the understanding of frequency regulation.

In the 18th century, John Harrison, in his quest to solve the problem of longitude, developed increasingly sophisticated marine chronometers. This included temperature-compensated balances that preserved oscillatory stability over long voyages. Abraham-Louis Breguet advanced the field further with inventions such as the tourbillon and natural escapement. These were both aimed at reducing positional errors and refining the control of frequency. Collectively, these early innovators established the principles that would guide the pursuit of accuracy through mastery of oscillation and frequency (The quest for accuracy at Fratello).

Longines made its own contributions to this field. They were already using high-frequency movements in stopwatches by 1914. The calibre 19.73N had a frequency of 36,000 vibrations per hour. This allowed the timing of events to a tenth of a second. This expertise predated other modern high-beat watches by decades. The transition from specialist stopwatches to much smaller wristwatches was a major engineering leap. The main challenge was not just making a small, fast-beating movement. It was making one that was also reliable and durable for daily wear. It took decades for the watchmaking industry to develop a commercially viable high-frequency wristwatch (Longines 19.73N at Teddy).

The Longines Ultra-Chron

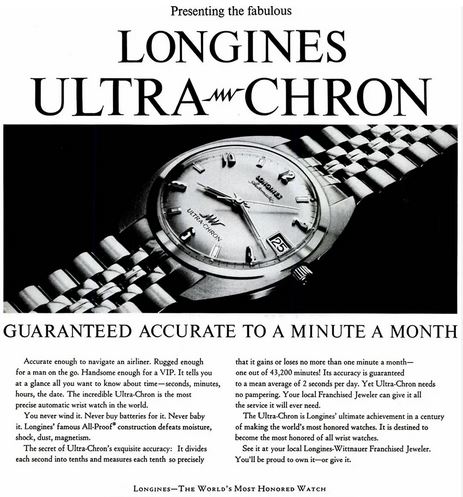

The original Longines Ultra-Chron launched in 1967. Longines boldly marketed it as “the world’s most accurate watch”. The claim promised accuracy to within one minute per month, which equates to about two seconds per day. The watch was a response to the “horological arms race” of the 1960s. This competition involved brands vying for chronometer records. Girard-Perregaux was first to market with a production high-frequency watch in 1966, and Seiko followed in early 1967. The Ultra-Chron played a significant part in this wave of watchmaking innovation.

Its significance lies in its mass production and clever marketing plan. It was an early attempt to bring high-frequency technology to a wider market. The collection included dress watches, field watches, and divers. The 1968 Ultra-Chron Diver was reportedly the first high-frequency dive watch. This cemented its place in history. Longines’ “world’s most accurate watch” claim was a marketing triumph. However, the Quartz Crisis that followed put an end to this mechanical arms race.

Longines Ultra-Chron movements and production

The original collection was in production from 1967 to 1974. The movements were the heart of the watches. According to the Ranfft database, the famous in-house automatic Calibre 431 had a frequency of 36,000 vph, 25 jewels and a 42-hour power reserve. It was also adjusted in four positions and for temperature. It used a dry molybdenum disulphide lubricant, which provided greater longevity than traditional oils. Other calibres were also in use. The calibre 430 had 17 jewels. Later in production, Longines introduced slower movements. Calibres 664x and 665x had a frequency of 28,800 vph.

This happened as the Quartz Crisis began to settle in. The accuracy of the new quartz watches made the mechanical high-frequency movement seem redundant. As a result, the high-beat revolution didn’t catch on so much beyond the early ’70s, although the Ultra-Chron did remain in production into the 1970s. Longines discontinued the calibre 431 in the early 1970s. This reflected the brand’s reaction to the quartz crisis. Longines shifted its focus to more standard, mass-produced calibres. This was necessary to ensure the company’s survival and foreshadowed its eventual absorption into the Swatch Group.

The Ultra-Chron revival

Longines revived the Ultra-Chron in 2022 as a faithful re-edition of the 1968 Ultra-Chron Diver. It features a cushion case, a high-frequency movement and is chronometer-certified. The new movement is the Calibre L836.6. According to WatchBase, it is an automatic movement with a frequency of 36,000 vph. It has 25 jewels, a silicon balance spring and a 52-hour power reserve.

Appeal to collectors

The vintage Longines Ultra-Chron is a highly collectable piece, appreciated for its historical significance. Collectors appreciate the brand’s contribution to the development of a high-frequency movement. The Ultra-Chron offers a great variety. Their designs can range from dressy to sporty. The original “World’s Most Accurate Watch” marketing claim is also a strong selling point.

Related content

Longines official website.

Leave a Reply